(English text available)

#paroladartista #intervistaartista #elenagrossi

▼scroll down for English text

Gabriele Landi: Quando hai recepito i primi sintomi di appartenenza alla dimensione dell’arte?

Elena Grossi: Ciao Gabriele, ho sentito di appartenere alla dimensione dell’arte solo dopo aver preso coscienza di appartenere, prima di tutto e più in generale, ad una dimensione creativa. Sono figlia unica, nata e cresciuta in un paese della campagna emiliana, in un contesto spazioso e strettamente connesso con la natura dal quale ho assorbito un modo di vivere lento e libero. La mia infanzia è stata segnata da un grande sogno, quello di diventare astronauta, ma soprattutto da quello di volare, un desiderio ambizioso e remoto, lo so, che ha in qualche modo scatenato la mia propensione verso la ricerca dell’impossibile. Da piccola disegnavo sempre, ogni scena e ogni figura erano spesso (e insolitamente) raffigurate dall’alto, come se il mio punto di vista sul mondo fosse già, appunto, aereo. Credo di aver capito proprio in quel periodo che la dimensione creativa (che esploravo anche con la materia, con la musica e con il gioco) sarebbe rimasta il mio unico mezzo per sottrarmi alle limitazioni imposte dalla quotidianità e dalla mia natura di essere umano. I “sintomi” dell’appartenenza alla dimensione dell’arte sono arrivati solo più tardi, non appena ho realizzato quelle che considero le mie prime opere ufficiali, quelle – per così dire – che hanno dato l’avvio al mio percorso di artista. Traducendo in immagini il mio universo interiore ho capito che anch’io avrei potuto occupare un posto nell’ambiente artistico, ma non riuscendo inizialmente ad esporre i miei lavori, la cosa rimaneva segreta, a senso unico, e ciò mi causava turbamento e incompletezza. Il percorso espositivo, si sa, è qualcosa di complicato, però per quanto mi riguarda è stato proprio attraverso quest’ultimo che ho sentito e sento ogni volta completarsi il mio bisogno di appartenenza all’arte, in primis perché a percepirmi artista (o “creatrice di immagini”, che è ancora più bello) sono io stessa, di conseguenza perché in questo modo offro anche agli altri la possibilità di riconoscermi come tale.

Gabriele Landi: Quale è stato il tuo iter formativo?

Elena Grossi: Il mio percorso formativo è iniziato parallelamente alle scuole medie, durante le quali ho frequentato per tre anni un corso di chitarra classica alla Scuola di Musica CEPAM, che ho poi interrotto dopo aver deciso di iscrivermi al Liceo Artistico Gaetano Chierici di Reggio Emilia continuando a suonare da autodidatta, cosa che tutt’oggi porto avanti anche se con meno insistenza di allora. Durante gli anni del liceo frequentavo la sezione moda, studiavo materie come progettazione, tessitura, stampa e confezione degli abiti, e devo ammettere che per tutti quegli anni ho creduto che quello sarebbe stato il mio futuro vista la mia inclinazione al disegno. Non so esattamente cosa sia successo, ma il cambio di rotta è avvenuto nel 2013, a 18 anni, anno in cui mi sono iscritta, dopo soli due mesi dalla maturità, all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna. Non è stata una decisione, è stato come un richiamo del tutto naturale, attrazione pura, una di quelle cose che si fanno e basta. Lì mi sono laureata in Pittura nel 2017 e poi in Arti Visive nel 2020, dopo aver scelto di proseguire gli studi presso la Cattedra di Luca Caccioni, sempre all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna. Ho iniziato la mia attività espositiva a vent’anni, di conseguenza gli anni in accademia, specialmente gli ultimi, hanno arricchito notevolmente la mia visione sul modo di relazionarmi con lo spazio, di fare ricerca, di sperimentare tecniche diverse, oltre che a creare un continuo scambio (e non confronto) con il lavoro di studenti provenienti da tutto il mondo. La fotografia poi, studiata e in un certo senso “scoperta” nel 2016 con la lettura de La camera chiara di Roland Barthes, è stata una folgorazione. Studiare per me è stato anche e soprattutto viaggiare: sono stata pendolare per dodici lunghi anni, ma questa è un’altra storia…

Gabriele Landi: Le tue fotografie mostrano una forte matrice pittorica, qual’è il tuo approccio a questo media?

Elena Grossi: Mi piace pensare, metaforicamente, che la pittura sia stata per me una crisalide, un passaggio obbligato, una pelle che ho dovuto abbandonare per seguire la mia metamorfosi creativa. Avendo ricevuto inizialmente una formazione pittorica, le mie prime sperimentazioni sono nate sotto forma di dipinti, niente di più scontato. Se dipingi sei un pittore, se lavori la materia sei scultore, se scatti fotografie un fotografo, ecc., ma posso confessare di aver sempre percepito su di me l’etichetta di “pittrice” come un po’ stretta. Forse può essere considerato un punto a mio favore, forse no, fatto sta che la mia mano è camaleontica, cioè riesce ad assumere facilmente identità diverse, come se a dipingere o a disegnare potesse essere stato ogni volta qualcun altro. A questo si aggiunge il fatto che per mia natura detesto essere rinchiusa all’interno di qualunque definizione, tendo ad essere sfuggente, di conseguenza credo di aver trovato la mia dimensione nell’uso di media differenti o, perché no, ibridi. Nello specifico cerco sempre di adattare la tecnica al concetto, non viceversa. Prediligo la fotografia per tanti motivi, tra cui quello – a differenza della pittura – di poterne conservare digitalmente più copie (sono molto spaventata dall’idea di poter perdere le cose a cui tengo). Se i miei lavori mostrano una forte matrice pittorica è perché desidero che se ne senta l’eco e poi perché mi interessa trasgredire la funzione di base di dispositivi come scanner, computer e macchina fotografica per ricreare una sorta di illusione proprio tra le tecniche stesse. L’illusione infatti è uno dei temi centrali della mia ricerca: a prima vista tutto appare come qualcosa che poi si rivela essere tutt’altro.

Gabriele Landi: L’aspetto illusorio è solo legato all’apparenza o anche ad altri aspetti di quello che fai. Mi piacerebbe chiederti di dire qualcosa di più su questo lato del tuo lavoro?

Elena Grossi: Nel mio lavoro l’aspetto illusorio va oltre l’apparenza, anche perché i due termini potrebbero funzionare come sinonimi. Mi interessa principalmente l’aspetto ambiguo, distorto e paradossale che l’illusione porta con sé (mi riferisco ad esempio a fenomeni ottici come Fata Morgana oppure al fatto che guardando le stelle quello che vediamo veramente sono questi oggetti così com’erano milioni di anni fa). I miei lavori hanno spesso a che fare con il binomio realtà-finzione, possibile-impossibile, presenza e assenza. Tutto si svolge all’interno di una dimensione utopica, avvolta dal clima sospeso della visione. L’osservatore si imbatte dunque in contesti solitari, metafisici e atemporali. Sperimentare l’illusione significa sperimentare un tipo di visionarietà creata dalla nostra mente per ingannarci facendo apparire come reali situazioni comunemente ritenute impossibili. Può darsi che l’interesse per l’illusione sia legato alla mia convivenza con la sinestesia, una condizione neurologica dove la stimolazione di un senso innesca automaticamente le esperienze di un secondo, come se il mio cervello fosse ingannato – appunto – da un’illusione, un incantesimo. La mia idea di arte è dunque anche strettamente connessa con quella di magia, “magico” per me equivale a “possibile”: il regno della magia, così come quello dell’immaginazione, rappresenta un tentativo di manipolare e dominare a piacimento la realtà circostante. Ciò spiega la tendenza a soffermarmi prima di tutto sulla necessità di crearmi un orizzonte altro, intimo e interiore. Un incrocio tra “landscapes” e “mindscapes”, ovvero tra geografie terrestri e geografie mentali, tra ciò che è e ciò che potrebbe diventare. La realtà che mi circonda non mi corrisponde, perciò tendo ad aggrapparmi (più o meno istintivamente) alla ricerca di un altrove, in modo da rendere più credibili universi lontani.

Gabriele Landi: Ti volevo chiedere di spiegare meglio che significato ha per te la: “dimensione utopica”?

Elena Grossi: Mi sento attratta da tutto ciò che so di non poter raggiungere se non attraverso i sogni ad occhi aperti, le cosiddette rêverie. Per rispondere (seppur metaforicamente) a questa sorta di richiamo so di avere a disposizione un solo mezzo: la consapevolezza del potere creativo inteso come libertà di rovesciare il senso comune delle cose, di mettere in discussione la realtà, di padroneggiarla modellandola a piacimento. Ogni utopia è nota per essere qualcosa che, paradossalmente, esiste senza esistere e che ci permette di vedere le cose anche dove non ci sono. La “dimensione utopica” che spesso inseguo, quindi, ha per me un significato di salvezza e di rifugio allo stesso tempo. È come se ri-creando spazi inediti e originali attraverso i territori dell’arte ritrovassi il senso di una ricerca che conduce ad una meta puramente idealistica, vagamente leggendaria e intangibile. Questa “dimensione” di cui parliamo ha anche il significato di fuga perché l’invito che rivolgo all’osservatore è sempre quello di andare al di là, di immergersi e disperdersi nel fascino dell’altrove, dell’ignoto. Risulta quindi difficile parlare di utopie senza parlare anche di distanza: l’aumento della distanza (fisica, emotiva, temporale, spaziale) nei confronti di ciò che ci attrae è proporzionale alla suggestione che ne deriva.

Gabriele Landi: A tale proposito ti volevo chiedere di parlare della dimensione temporale dei tuoi lavori?

Elena Grossi: Le immagini, per loro natura, sfuggono allo scorrere del tempo ed è forse questa la loro caratteristica più affascinante. Il tempo le tocca solo perché le invecchia o le altera da un punto di vista chimico-materico, ma ciò che mostrano è destinato ad essere immutabile ed eterno. Nessuna immagine pensata per rimanere tale si è mai evoluta. Tutto, al suo interno, è sempre congelato in un’immobile fissità. Che si tratti di figurazione, astrazione, pittura o fotografia, non si assiste mai a uno sviluppo, a un “cambio di scena”, così come invece accade alle immagini in movimento, quindi al video, al cinema, oppure in ambito musicale. Nei miei lavori ciò viene semplicemente rimarcato. Mentre lavoravo a Case départ, ad esempio, una serie fotografica iniziata nel 2017, mi sono accorta che ribaltando a 360° le porzioni di una stessa immagine attraverso collage digitali, gli orologi di campanili, castelli e architetture varie, nell’immagine finale perdevano le lancette restituendo cerchi vuoti contornati da cifre quasi illeggibili, come a rimarcare la propria atemporalità, il proprio rifiuto del tempo. Mi piace raccontare di luoghi che non hanno né inizio, né fine: non solo incollocabili, ma anche immortali. Basta uscire dalla nostra atmosfera perché le cose cambino radicalmente: così come il concetto di alto e di basso non esiste più nello spazio, allo stesso modo il concetto di tempo nei miei lavori si perde.

Gabriele Landi: Lo spingere le immagini fino all’assurdo al paradosso mi sembra essere uno dei punti di forza di quello che fai. Per toccare questo limite adotti un metodo o tutto avviene a livello istintivo?

Elena Grossi: Esatto, poi però esiste anche un lato della mia ricerca che si discosta un po’ da questa “ossessione” per l’assurdo e il paradossale. Ultimamente sto esplorando i territori dell’intelligenza artificiale con vari progetti ed esperimenti in cui l’apprendimento automatico da parte della macchina interferisce con l’intervento umano. Spesso indago anche le possibilità di metamorfosi dell’immagine attraverso l’acqua, alternando processi di immersione ed emersione, oppure utilizzando la polvere… Tornando alla domanda, sarei tentata a dire che per quanto riguarda i concetti e le idee tutto avviene a livello istintivo per il semplice fatto che nel mio caso la tendenza all’illusorio è qualcosa di spontaneo. Se invece parliamo del momento successivo in cui do forma a ciò che vedo dentro di me, quindi del momento della creazione vera e propria, allora no, quel processo non c’entra nulla con l’istinto. Il mio “metodo” somiglia più a quello di un regista, di un architetto o progettista perché mi interessa l’operazione del costruire, l’operazione dello scomporre e del ricomporre le immagini attraverso il processo metaforico del “come se” fino a quando non assumono le sembianze desiderate. Essendo caratterialmente molto riflessiva ho bisogno di studiare, di pianificare le cose prima di procedere con sicurezza, come se ogni opera fosse composta da un insieme di ingranaggi da incastrare tra loro per poter funzionare. Niente è lasciato al caso nei miei lavori, non riesco proprio a tralasciare i dettagli.

Gabriele Landi: Ti volevo chiedere di parlare di questi lavori che fai usando l’intelligenza artificiale spiegando come la usi e in che modo interagisce con il tuo lavoro?

Elena Grossi: Mi sono avvicinata al mondo dell’intelligenza artificiale qualche anno fa, incuriosita dal complesso rapporto tra uomo e macchina. Per il momento ho utilizzato software di apprendimento automatico, il cosiddetto machine learning, dove l’iterazione dell’utente influenza in parte il risultato finale che, essendo “elaborato” per metà dal cervello di un computer, è sempre imprevedibile. Si tratta di programmi progettati per ricevere input – come ad esempio una frase che descrive ciò che vorremmo ci venisse mostrato – in modo da poter “generare”, dopo averla processata, la nostra richiesta in termini visivi, cercando di avvicinarsi il più possibile alla realtà. Personalmente trovo interessante l’aspetto legato alla scrittura che sta alla base di queste operazioni (più scriviamo bene e più la resa è migliore), ma anche la velocità con cui, in certi casi, si possono ottenere risultati a dir poco sorprendenti. Nonostante tutto sia basato sul calcolo, spesso si verificano errori e incomprensioni dovute alla scarsa conoscenza dei linguaggi umani da parte dei sistemi intelligenti. La mia prima serie di lavori realizzati con l’IA, (How to) Tell the Machines Goodnight, mette proprio in evidenza la difficoltà di elaborare il linguaggio naturale – nel mio caso il dialetto emiliano – a causa dell’ambiguità che lo caratterizza. In One of Us invece ho riflettuto sul concetto di autoritratto, mimesi e identità imponendo la mia presenza tra volti estremamente realistici di sconosciuti prodotti da un algoritmo generativo. Adesso sto lavorando ad altri tre progetti: La battaglia dei fiori sarà un tentativo di descrivere l’“immagine dei fiori” con centomila foto, ovvero tante quante il numero di fiori impiegati nell’omonimo evento tramite un processo di media cromatica che trasformerà ogni fiore in un singolo pixel; Ogni dove in cielo è paradiso, una raccolta di nuvole riconosciute come volti umani dal rilevamento facciale che esplora il tema della pareidolia; infine un bestiario di creature inverosimili immortalate senza l’uso della macchina fotografica. Il campo dell’IA è ancora molto limitato: salvare i file è l’unico modo per evitarne la cancellazione automatica da parte del software. Non voglio però né abbandonarlo né farlo prevalere sul resto.

Elena Grossi (Montecchio Emilia, 1994) è laureata in Pittura (2017) e in Arti Visive (2020) presso l’Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna. Interessata a diversi sistemi di rappresentazione con particolare attenzione alla fotografia e al riuso poetico di quest’ultima, nei suoi lavori riflette sui concetti di illusione, memoria e distanza. La continua ricerca della lontananza, spesso affidata al processo metaforico del “come se”, dà vita ad un ribaltamento percettivo in cui i frammenti del microcosmo quotidiano diventano visioni “altre”, portatrici di un senso dell’inaspettato, dell’inesplorato e di nuove letture dei fenomeni circostanti. Attraverso pochi elementi sempre capaci di diffondere un clima dal carattere interiore e parallelamente universale, il mondo si scompone e si ricompone ogni volta in modo tanto imprevedibile quanto sensibile. Il suo lavoro è stato esposto in gallerie d’arte e istituzioni pubbliche come Varna City Art Gallery, Varna, Bulgaria (2023); Holsum Gallery, Kansas City, USA (2023); RuptureXIBIT, Londra, Regno Unito (2023); GREEN DOOR artists space & gallery, Vienna, Austria (2022); DongGang Museum of Photography, Yeongwol, Corea del Sud (2022); Cittadellarte – Fondazione Pistoletto, Biella (2022); Lavì! City, Bologna (2022); Weltkunstzimmer, Düsseldorf, Germania (2021); Khodynka Gallery, Mosca, Russia (2021); RoCo, Rochester, USA (2021); CICA Museum, Gimpo, Corea del Sud (2021); SAMCA, Sofia, Bulgaria (2021); The Wall Space, Falkirk, Regno Unito (2020); Sct. Peders Kirke, Randers, Danimarca (2020); Das Provisorium, Monaco di Baviera, Germania (2019); Istituto Storico Parri, Bologna (2019); spazio microLive, Milano (2019); Fotografia Europea, Reggio Emilia (2016).

Sito web: https://elenagrossi.weebly.com

Instagram: @_elenagrossi

English text

Interview with Elena Grossi

#paroladartista #interviewartist #elenagrossi

Gabriele Landi: When did you first feel you belonged to the dimension of art?

Elena Grossi: Hi Gabriele, I felt that I belonged to the dimension of art only after I became aware that I belonged, first and foremost, to a creative dimension. I am an only child, born and raised in a village in the Emilian countryside, in a spacious context closely connected with nature from which I absorbed a slow and free way of life. My childhood was marked by a great dream, that of becoming an astronaut, but above all by that of flying, an ambitious and remote desire, I know, which somehow triggered my propensity towards the pursuit of the impossible. As a child, I used to draw all the time, every scene and every figure were often (and unusually) depicted from above, as if my view of the world was already, indeed, aerial. I think I realised at that time that the creative dimension (which I also explored with matter, music and play) would remain my only means of escaping the limitations imposed by everyday life and my nature as a human being. The ‘symptoms’ of belonging to the dimension of art only came later, as soon as I created what I consider to be my first official works, the ones – so to speak – that started my journey as an artist. By translating my inner universe into images, I realised that I, too, could occupy a place in the artistic environment, but as I was initially unable to exhibit my work, it remained a secret, a one-way street, and this caused me upset and incompleteness. The exhibition process, as you know, is something complicated, but as far as I am concerned, it was precisely through it that I felt and still feel my need to belong to art complete, firstly because I perceive myself as an artist (or ‘creator of images’, which is even better), and secondly because in this way I also offer others the opportunity to recognise me as such.

Gabriele Landi: What was your educational path?

Elena Grossi: My training path began in parallel with middle school, during which I attended a classical guitar course at the CEPAM Music School for three years, which I then interrupted after deciding to enrol at the Gaetano Chierici Art School in Reggio Emilia, continuing to play as a self-taught musician, something I still do today, albeit with less insistence than then. During my high school years I attended the fashion section, studying subjects such as design, weaving, printing and garment making, and I must admit that for all those years I believed that would have been my future given my inclination towards drawing. I don’t know exactly what happened, but the change of direction came in 2013, at the age of 18, when I enrolled, just two months after graduating from high school, at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. It was not a decision, it was like a completely natural call, pure attraction, one of those things you just do. There I graduated in Painting in 2017 and then in Visual Arts in 2020, after choosing to continue my studies at the Luca Caccioni Chair, also at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. I started exhibiting when I was 20 years old, consequently the years at the academy, especially the last ones, have greatly enriched my vision on how to relate to space, to do research, to experiment with different techniques, as well as to create a continuous exchange (and not comparison) with the work of students from all over the world. Photography then, studied and in a way ‘discovered’ in 2016 with the reading of The Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes, was a thunderbolt. Studying for me was also and above all travelling: I was a commuter for twelve long years, but that’s another story…

Gabriele Landi: Your photographs show a strong pictorial matrix, what is your approach to this media?

Elena Grossi: I like to think, metaphorically, that painting was a chrysalis for me, an obligatory passage, a skin I had to leave behind to follow my creative metamorphosis. Having been initially trained as a painter, my first experiments came in the form of paintings, nothing more obvious. If you paint you are a painter, if you work with material you are a sculptor, if you take photographs you are a photographer, etc., but I can confess that I have always perceived the label ‘painter’ as a bit of a squeeze. Perhaps this can be seen as a point in my favour, perhaps not, the fact is that my hand is chameleon-like, that is, it can easily take on different identities, as if someone else could have painted or drawn it each time. Added to this is the fact that by my nature I hate being enclosed within any definition, I tend to be elusive, and consequently I think I have found my dimension in the use of different media or, why not, hybrids. Specifically, I always try to adapt the technique to the concept, not vice versa. I prefer photography for many reasons, one of which – unlike painting – is that I can digitally preserve multiple copies (I am very afraid of losing things I care about). If my works show a strong pictorial matrix, it is because I want its echo to be heard and then because I am interested in transgressing the basic function of devices such as scanners, computers and cameras to recreate a kind of illusion between the techniques themselves. Illusion is in fact one of the central themes of my research: at first sight everything appears to be something that then turns out to be something else entirely.

Gabriele Landi: Is the illusory aspect only related to appearance or also to other aspects of what you do. I would like to ask you to say something more about this side of your work?

Elena Grossi: In my work, the illusory aspect goes beyond appearance, also because the two terms could function as synonyms. I am mainly interested in the ambiguous, distorted and paradoxical aspect that illusion brings with it (I refer for example to optical phenomena such as Fata Morgana or to the fact that when we look at the stars what we really see are these objects as they were millions of years ago). My works often deal with the binomial reality-fiction, possible-impossible, presence and absence. Everything takes place within a utopian dimension, wrapped in the suspended atmosphere of vision. The observer thus encounters solitary, metaphysical and timeless contexts. To experience the illusion is to experience a type of visionarity created by our mind to deceive us by making situations commonly thought impossible appear as real. It may be that my interest in illusion is linked to my coexistence with synesthesia, a neurological condition where the stimulation of one sense automatically triggers the experiences of a second, as if my brain were tricked – precisely – by an illusion, a spell. My idea of art is therefore also closely connected with that of magic, ‘magic’ for me equals ‘possible’: the realm of magic, like that of imagination, represents an attempt to manipulate and dominate the surrounding reality at will. This explains my tendency to dwell first and foremost on the need to create for myself another, intimate and inner horizon. A cross between ‘landscapes’ and ‘mindscapes’, that is, between terrestrial geographies and mental geographies, between what is and what could become. The reality that surrounds me does not correspond to me, so I tend to cling (more or less instinctively) to the search for an elsewhere, in order to make distant universes more credible.

Gabriele Landi: I wanted to ask you to better explain what does the: “utopian dimension”?

Elena Grossi: I feel attracted by everything I know I cannot reach except through daydreams, so-called reveries. To respond (albeit metaphorically) to this sort of call, I know I have only one means at my disposal: the awareness of creative power understood as the freedom to overturn the common sense of things, to question reality, to master it by modelling it at will. Every utopia is known to be something that, paradoxically, exists without existing and that allows us to see things even where they are not there. The ‘utopian dimension’ that I often pursue, therefore, has for me a meaning of salvation and refuge at the same time. It is as if by re-creating new and original spaces through the territories of art I rediscover the sense of a quest that leads to a purely idealistic, vaguely legendary and intangible goal. This ‘dimension’ of which we speak also has the meaning of escape because the invitation I address to the observer is always to go beyond, to immerse and disperse oneself in the fascination of elsewhere, of the unknown. It is therefore difficult to talk about utopias without also talking about distance: the increase in distance (physical, emotional, temporal, spatial) with regard to what attracts us is proportional to the suggestion that derives from it.

Gabriele Landi: On this subject, I wanted to ask you about the temporal dimension of your work?

Elena Grossi: Images, by their nature, escape the passage of time, and this is perhaps their most fascinating characteristic. Time touches them only because it ages them or alters them from a chemical-material point of view, but what they show is destined to be immutable and eternal. No image designed to remain so has ever evolved. Everything within it is always frozen in an immobile fixity. Whether it is figuration, abstraction, painting or photography, there is never a development, a ‘change of scene’, as there is with moving images, i.e. video, film, or music. In my work, this is simply emphasised. While I was working on Case départ, for example, a photographic series started in 2017, I realised that when I flipped the portions of the same image 360° through digital collages, the clocks of bell towers, castles and various architectures lost their hands in the final image, giving back empty circles surrounded by almost illegible figures, as if to emphasise their timelessness, their rejection of time. I like to tell of places that have neither beginning nor end: they are not only relocatable, but also immortal. It is enough to leave our atmosphere for things to change radically: just as the concept of high and low no longer exists in space, in the same way the concept of time is lost in my works.

Gabriele Landi: Pushing images to the point of absurdity to paradox seems to me to be one of the strengths of what you do. Do you adopt a method to touch this limit or does everything happen on an instinctive level?

Elena Grossi: Exactly, but there is also a side to my research that deviates a bit from this ‘obsession’ with the absurd and paradoxical. Lately I have been exploring the territories of artificial intelligence with various projects and experiments in which machine learning interferes with human intervention. I also often investigate the possibilities of image metamorphosis through water, alternating processes of immersion and emersion, or using dust… Returning to the question, I would be tempted to say that as far as concepts and ideas are concerned everything happens on an instinctive level for the simple fact that in my case the tendency towards the illusory is something spontaneous. If, on the other hand, we are talking about the later moment in which I give form to what I see within me, hence the moment of actual creation, then no, that process has nothing to do with instinct. My ‘method’ is more like that of a director, an architect or designer because I am interested in the operation of building, the operation of breaking down and recomposing images through the metaphorical process of ‘as if’ until they take on the desired appearance. Being characteristically very reflective, I need to study, to plan things out before proceeding with certainty, as if each work were made up of a set of gears that must fit together in order to function. Nothing is left to chance in my work, I just can’t leave out the details.

Gabriele Landi: I wanted to ask you about the work you do using artificial intelligence, explaining how you use it and how it interacts with your work?

Elena Grossi: I approached the world of artificial intelligence a few years ago, intrigued by the complex relationship between man and machine. For the time being, I used machine learning software, where the user’s iteration partly influences the final result, which, being half ‘processed’ by a computer brain, is always unpredictable. These are programmes designed to receive input – such as a sentence describing what we would like to be shown – so that, after processing it, they can ‘generate’ our request in visual terms, trying to come as close as possible to reality. Personally, I find the writing aspect behind these operations interesting (the better we write, the better the output), but also the speed with which, in certain cases, surprising results can be achieved. Although everything is based on calculation, errors and misunderstandings often occur due to the lack of knowledge of human languages on the part of intelligent systems. My first series of works realised with AI, (How to) Tell the Machines Goodnight, highlights precisely the difficulty of processing natural language – in my case the dialect of Emilia – due to its ambiguity. In One of Us, on the other hand, I reflected on the concept of self-portrait, mimesis and identity by imposing my presence among extremely realistic faces of strangers produced by a generative algorithm. I am now working on three more projects: The Battle of the Flowers will be an attempt to describe the ‘image of flowers’ with one hundred thousand photos, that is, as many as the number of flowers employed in the event of the same name through a process of chromatic averaging that will transform each flower into a single pixel; Everywhere in Heaven is Paradise, a collection of clouds recognised as human faces by facial detection that explores the theme of pareidolia; and finally a bestiary of unlikely creatures immortalised without the use of a camera. The field of AI is still very limited: saving files is the only way to avoid their automatic deletion by the software. However, I neither want to abandon it nor let it take precedence over the rest.

Elena Grossi (Montecchio Emilia, 1994) graduated in Painting (2017) and Visual Arts (2020) at the the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna. Interested in different systems of representation with particular attention to photography and its poetic reuse, in her works she reflects on the concepts of illusion, memory and distance. The continuous search for distance, often entrusted to the metaphorical process of ‘as if’, gives rise to a perceptive reversal in which fragments of the everyday microcosm become ‘other’ visions, bearers of a sense of the unexpected, of the unexplored and of new readings of surrounding phenomena. Through a few elements always capable of spreading a climate of inner and at the same time universal character, the world is decomposes and recomposes itself each time in a way that is as unpredictable as it is sensitive. His work has been exhibited in art galleries and public institutions such as Varna City Art Gallery, Varna, Bulgaria (2023); Holsum Gallery, Kansas City, USA (2023); RuptureXIBIT, Londra, Regno Unito (2023); GREEN DOOR artists space & gallery, Vienna, Austria (2022); DongGang Museum of Photography, Yeongwol, Corea del Sud (2022); Cittadellarte – Fondazione Pistoletto, Biella (2022); Lavì! City, Bologna (2022); Weltkunstzimmer, Düsseldorf, Germania (2021); Khodynka Gallery, Mosca, Russia (2021); RoCo, Rochester, USA (2021); CICA Museum, Gimpo, Corea del Sud (2021); SAMCA, Sofia, Bulgaria (2021); The Wall Space, Falkirk, Regno Unito (2020); Sct. Peders Kirke, Randers, Danimarca (2020); Das Provisorium, Monaco di Baviera, Germania (2019); Istituto Storico Parri, Bologna (2019); spazio microLive, Milano (2019); Fotografia Europea, Reggio Emilia (2016).

web: https://elenagrossi.weebly.com

Instagram: @_elenagrossi

(How to) Tell the Machines Goodnight, 2021, stampe inkjet su tela e carta blue back, varie dimensioni – installation view (rendering)

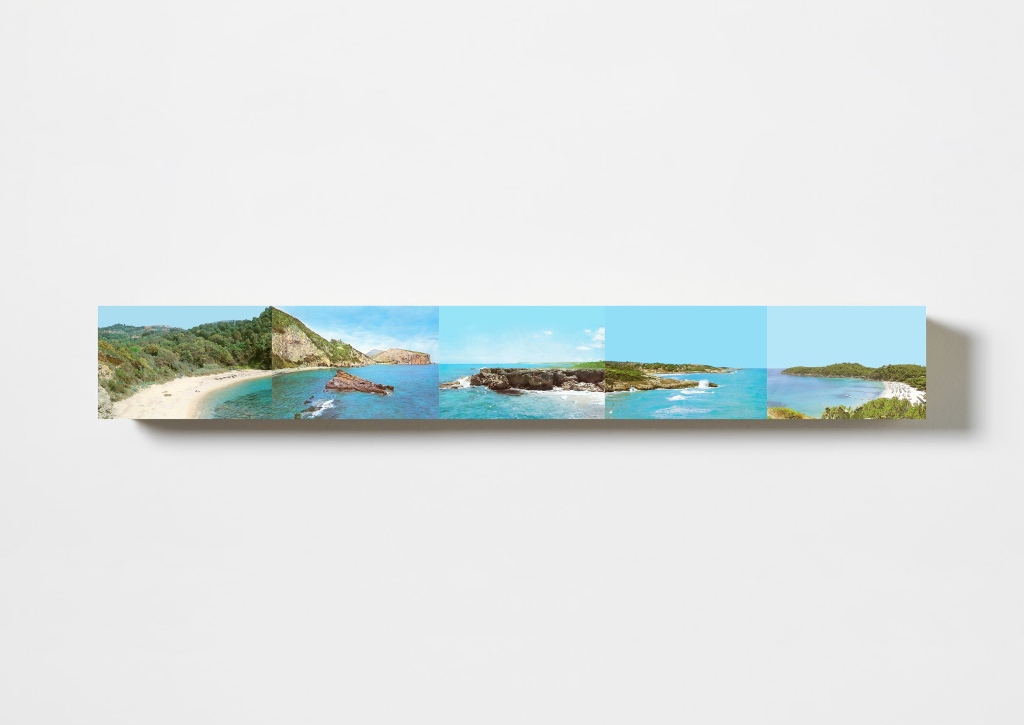

In linea d’aria, 2019, cartoline postali, collage digitale, stampa inkjet su carta Hahnemühle Photo Luster montata su legno, 10×73,5 cm

Lo sguardo del viaggiatore immobile, 2023, Polaroid realizzata a mano, 10,7×9 cm – Crediti_immagine originale di NASA, NOAO, ESA, the Hubble Helix Nebula Team, M. Meixner (STScI), and T.A. Rector (NRAO), manipolat

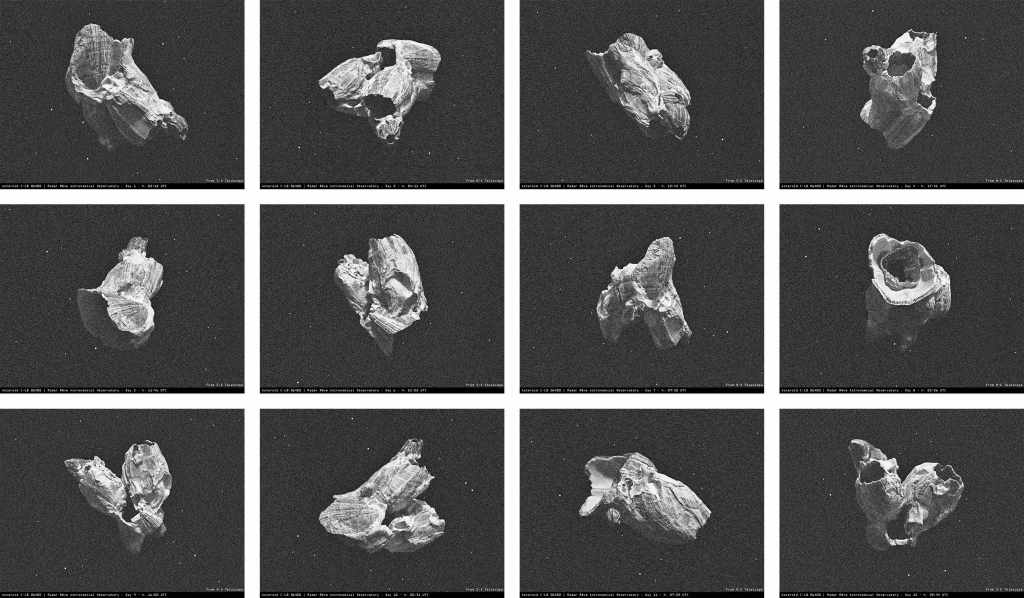

Radar Rêve, 2019, fotografie, stampe fine-art su carta Hahnemühle Photo Luster montate su dibond, 66×110 cm (20×26 cm ognuna)

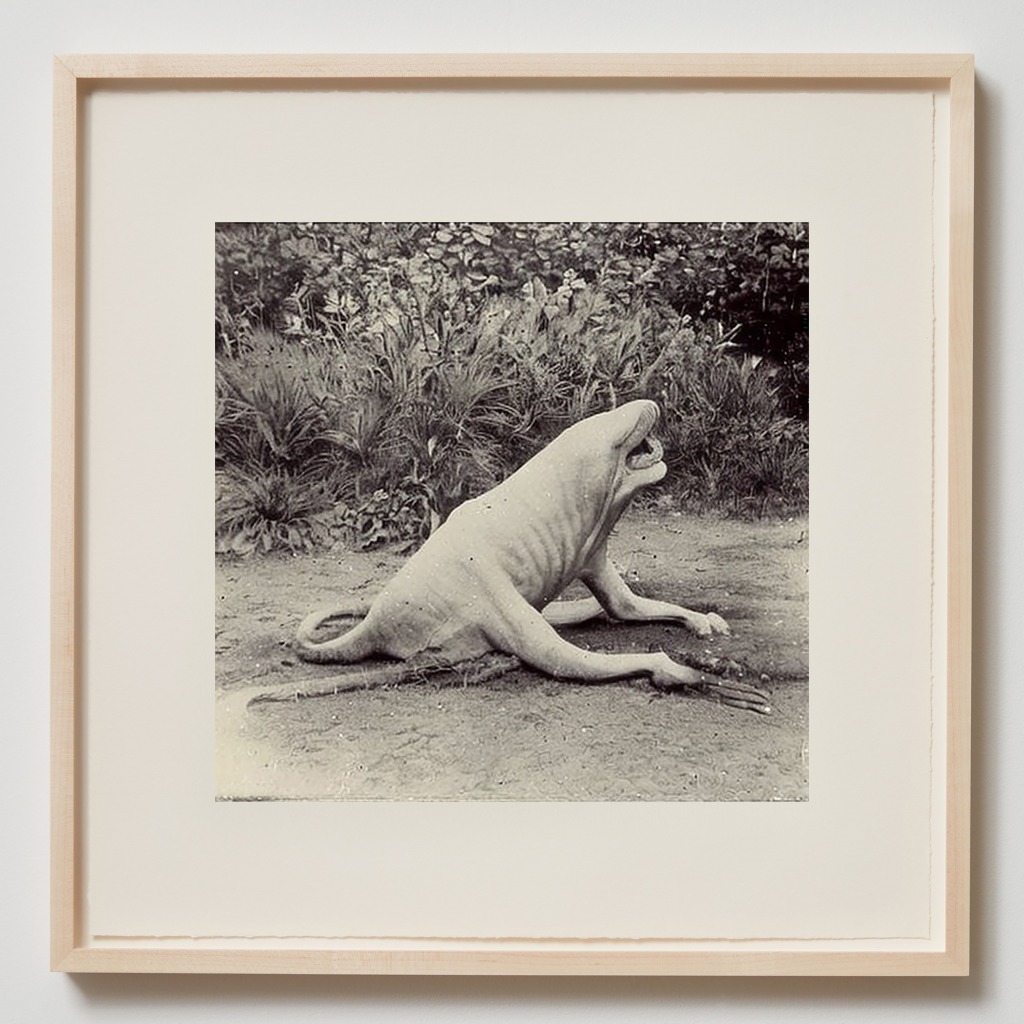

Senza titolo (Bestiario), 2023, stampa su carta baritata, 46×46 cm

Stardust, 2017, polvere e intonaco su lastra di plexiglass, inchiostro, scansione, stampa su laminato e plexiglass, ø 200 cm – installation view (rendering) (2)